Queer Rage

Queer rage refers to the collective anger and frustration experienced by individuals within the LGBTQ+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and other non-heteronormative identities) community in response to various forms of discrimination, prejudice, inequality, or injustice. Our artifacts show that rage sometimes feels uncontrollable but can also catalyze empowerment and growth. These artifacts show anger channeled into constructive actions, building supportive communities, and creating spaces for self-expression. Through this, queer rage can contribute to resilience and positive change. It is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon; it is a testament to the complexity and beauty of the human experience.

This photo was taken on April 22nd, 1990, by Genyphyr Novak at a staged “die-in” in front of the headquarters of the American Medical Association in Chicago, Illinois. The people depicted in the photo of this “die-in” were activists from ACT UP, a well-known organization fighting for an end to the AIDS epidemic. At this event, a group of protestors staged a small play about the blood money (a term referencing the profiting off of people’s suffering and death) being taken by the large drug and insurance companies who refused to pay for certain AIDS treatments or cut off the policies of those diagnosed with AIDS (chicagomag.com). Members of the play then also “died” on the street and were outlined with chalk, refusing to move until they were arrested by police. Tying into our theme of queer emotion, this photo is a clear representation of queer rage. Rage is a common response to injustice, and that is exactly what these activists were responding to in this photo.

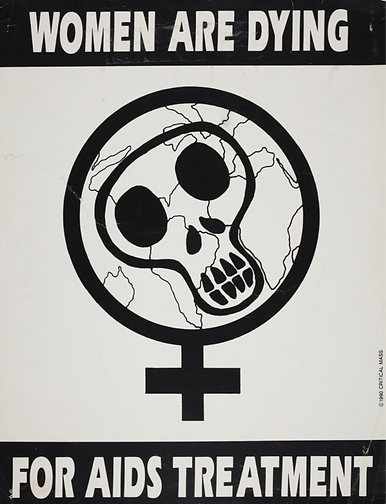

This artifact is a poster that was made to represent the rage that the LGBTQ+ community had to endure throughout history. In the exhibition made by Olivia Hingley, they showcase a series of queer posters that were made for a plethora of reasons, but they all share one common theme: rage. This specific poster has the symbol for a female with a skull on the inside of the circle with the text “WOMEN ARE DYING FOR AIDS TREATMENT.” It was made by Ellen Yellowbird, Josh Wells, Jordan Peimer, and Michael Fuller for the ACT-UP coalition in 1990. The ACT-UP coalition is known for being the main group against the AIDS crisis, and they spent many years fighting for more accessibility to AIDS treatment and care. This can be seen as important because of the fact that this poster was made for a cause, many LGBTQ+ individuals were struggling with this disease and not everyone wanted to acknowledge it. Rage is the main overall emotion behind this poster, people were angry that the government wasn’t helping much with the individuals affected by HIV and that can be seen through the expression of death shown in the poster. The depiction of the globe inside of the symbol is representative of the fact that this is a global issue, and can also speak to the universality of the anger experienced by the queer community in regards to this specific injustice.

“What’s Fair in Love and War” by Randy Shilts is an article about the military's acceptance and history with homosexuality in times of war. His article was published in a Newsweek magazine, in March of 1993. He had just released his newest book “Conduct Unbecoming: Gays and Lesbians in the U.S. Military, Vietnam to the Persian Gulf (1993),” but unfortunately, Shilts, 41 who had been made famous by his writing on AIDS had unfortunately developed AIDS himself. Diagnosed with HIV in 1985, Shilts eventually died of AIDS the following year(1994) at the age of 42. This article was one of his last written pieces and still holds valuable questions and insights on how the world interacts with queerness as a whole. The article was published through Newsweek. Based in New York City, Newsweek has been distributing weekly news magazines since 1933 and continues to publish articles. This specific article was a one-time publication, as Shilts mostly wrote for the San Fransisco Chronicle and stuck to coverage of the Bay area. Publishing the article in New York helped to deepen his impact during his last years. In this article, Shilts tackles what he spent much of his book talking about; the portrait of homosexuals in the military as it entered the country's conscience. He discusses how military culture has historically shaped a particular kind of homophobia, enabling mainstream readers to see lesbian and gay issues as matters of human rights and worthy of national and international priority. Shilts holds space for a multiplicity of emotions but ultimately, Shilts is angered by the history and irony that is the military's relationship with the queer community.

The short story “Lincoln Park” was written by Patricia Fullerton and submitted to the August-September 1972 issue of The Ladder, the publication of the Daughters of Bilitis. Founded in 1955, the Daughters of Bilitis was the first major organization for lesbians in the United States (Cohen 1). The piece was written by one of the many women who submitted their works to the magazine, and as such not much is known about her. She may have used a pseudonym to protect her identity. This issue was the last issue ever published by the Daughters after 16 years of the publication after tensions within the group caused the disbandment of the Daughters. The president at the time, Rita LaPorte, took possession of the 3,800-member mailing list for The Ladder, of which there were only two copies to ensure the women’s identities were protected, and she and Barbara Grier, editor-in-chief of The Ladder, continued to publish it until they ran out of funds (Gallo 159). Despite the tumultuous ending of the publication, it came from a place of love on all sides; Grier knew that the Daughters were falling apart, and she “wanted The Ladder to survive” (Gallo 161). This story is told from the perspective of a woman who is reflecting upon her time as a young girl frequenting the park by herself when she has free time. She noticed a woman who always sits alone, and one day, she saw this woman kiss another woman. Then, the girl is targeted by a man who first earned her trust by pretending to be an FBI agent, and he sexually assaulted her. She was rescued by this same woman who came barrelling in, yelling at the man until he ran away. Though the girl didn’t understand much at the time, she now understands the “love that [her] ‘park’ friend felt (Fullerton 20), her determination to protect that lonely kid. This illustrates queer rage; the woman saw with her own eyes the rottenness of the world, and she took it upon herself to stop it.